Go channels in Cpp, part 2

In this part 2 of the Go channel series, I will expand the Channel<T> class we developed to support multiple elements, range for loops and asynchronous operations.

Part one of this series, where we built a simple Go channel with similar synchronization behavior is available here.

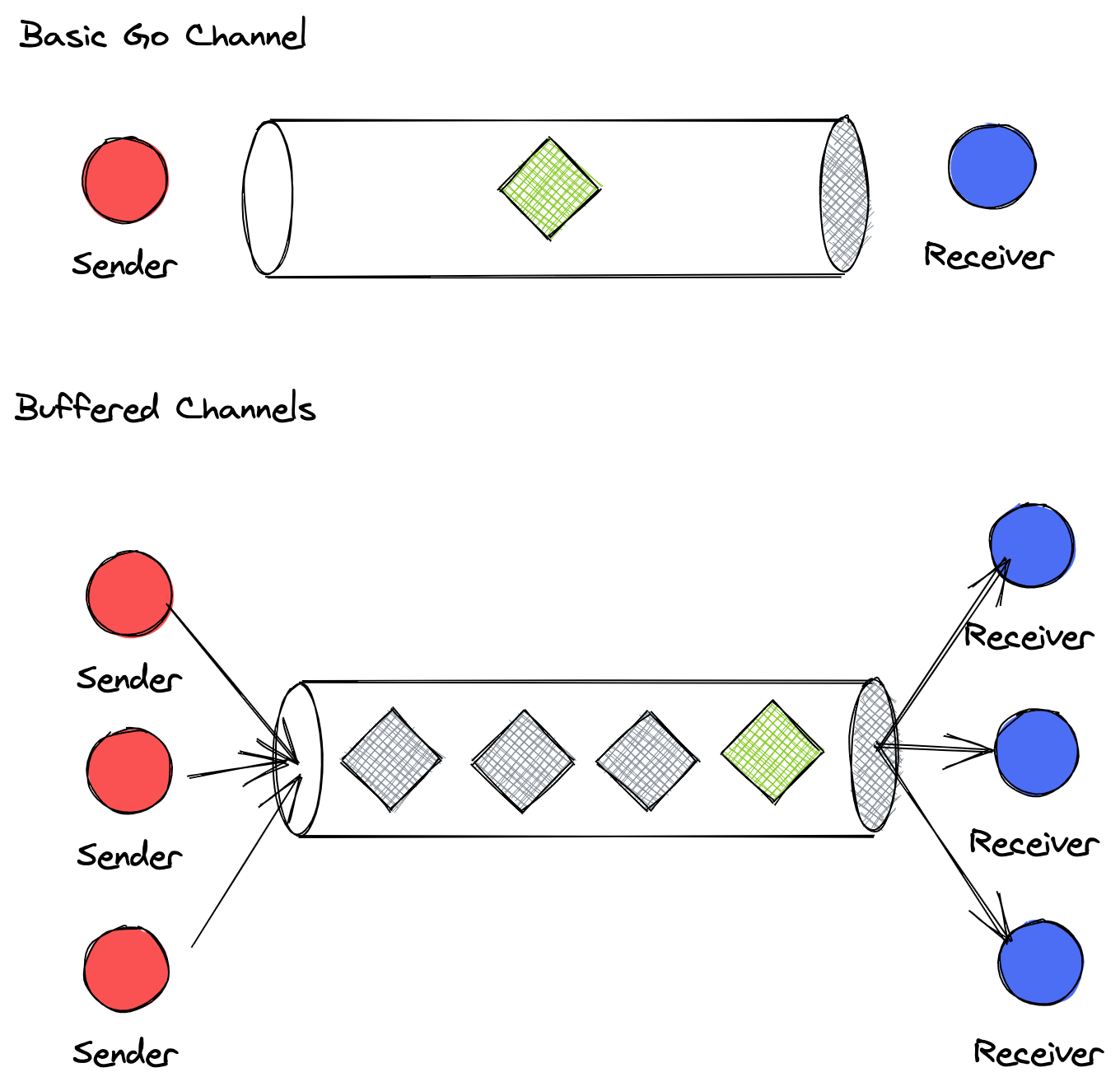

Buffered channels are desirable in many parallel applications such as work queues, worker/thread pools, MCMP (multiple consumers/producers) patterns.

Well designed, large scale complex concurrent systems are often built from a few fairly simple building blocks such as buffered channels. Even though these buffered channels are still constructed the same way in Go, they are actually entirely different in behavior from simple channels, and really behave differently. The objective for buffered channel is less so of synchronization, but more to deal with non-deterministic input/output “flow rate” into a system. As a result, in buffered channels, send/receive operations are non-blocking provided there is capacity in the channel. In addition, they have storage, whereas simple channel is more of a “pass-through” entity.

Buffered Channels

Go Example - A Buffered Channel

From part 1, we know that if a sender/receiver is not paired together, the channel send/receive will block indefinitely. As a result, if we run the following code, we should get a deadlock panic.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

queue := make(chan string)

queue <- "one"

queue <- "two"

close(queue)

for elem := range queue {

fmt.Println(elem)

}

}

▶ go run deadlock_1thread.go

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

/Users/blu/Repos/go-channels-in-cpp/go/deadlock_1thread.go:8 +0x59

exit status 2

To fix this, the blocking behavior on send needs to be changed to non-blocking. Buffered channel offers this. When a buffered channel has free capacity, the sends are asynchronous and returns right away, as it does not require an active receiver on the channel. To make a buffered channel, we provide a second argument of channel capacity when constructing the channel.

queue := make(chan string, 2)

With a buffered channel, the deadlock code no longer panics

▶ go run deadlock_1thread.go

one

two

Receive on a buffered channel behaves similar to a normal channel. If there are no items in the channel currently, the receive operation will block until something is available.

C++ Implementation

With that brief introduction, let’s return to C++ land to see what changes we need to make to implement similar behaviors.

Starting from the single element channel in our part 1 of this series, it is quite simple to support buffered channels by storing the elements in a STL container such as a double-ended queue via std::deque<T>:

we replace the m_val and m_has_value variables with a single data structure m_data of type std::deque<T>.

We can also use other STL containers such as a std::list, or a std::vector, I picked a queue since it closely mimics the channel in operation (inserting on one end, removing from the other end).

protected:

std::deque<T> m_data;

std::mutex m_mutex;

std::condition_variable m_cv;

Turned out, with this change, our send/receive logic also simplifies quite a bit - since we no longer need to use condition variable and extra flags to ensure that there is a proper sender/receiver pairing. Also note, we added a function empty() to return whether there is any data in the queue.

T receive()

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> the_lock(m_mutex);

m_cv.wait(the_lock, [this]

{

return !empty();

});

T val = std::move(m_data.front());

m_data.pop_front();

return val;

};

void send(T&& val)

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> the_lock(m_mutex);

m_data.emplace_back(val);

m_cv.notify_all();

};

bool empty() const {

return m_data.empty();

}

Our C++ test program has been updated to reflect the new buffered channel - where we send multiple items through the channel in a separate thread and attempt to receive them in the main thread

int main() {

Channel<std::string> chan;

std::cout << "Channel created.\n";

const auto capacity = 3;

// kick off thread to send

auto future = std::async(std::launch::async,

[&chan, capacity](){

{

auto t = timer("send thread");

for (size_t i = 0; i < capacity; ++i)

{

std::cout << THREADSAFE("send thread: sending ping " << i << "\n");

chan.send(THREADSAFE("ping "<<i));

std::cout << THREADSAFE("send thread: sending ping " << i << " done\n");

}

}

});

// receive

std::string val;

for (size_t i = 0; i < capacity; ++i)

{

std::cout << "main thread: calling receive:\n";

val = chan.receive();

std::cout << THREADSAFE("main thread: received " << val << std::endl);

}

future.get();

return 0;

}

The output is:

Channel created.

main thread: calling receive:

send thread: sending ping 0

send thread: sending ping 0 done

send thread: sending ping 1

send thread: sending ping 1 done

send thread: sending ping 2

send thread: sending ping 2 done

send thread took 0 s.

main thread: received ping 0

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 1

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 2

We got the desired behavior - the messages came in order, and also the send/receive are now happening asynchronously.

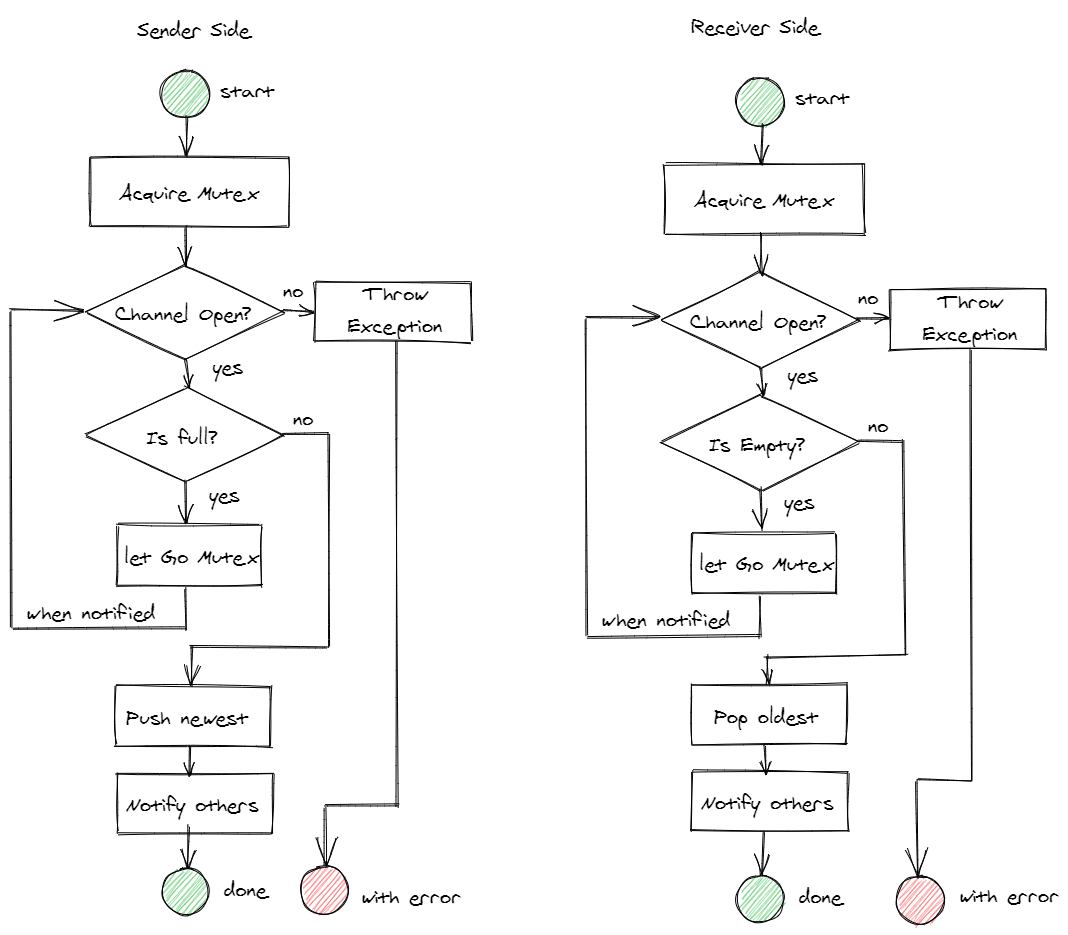

We need to implement a few additional features to complete our buffered channel:

- Track whether channel is currently open/closed - this requires adding a boolean state

- Add capacity to the channel so we do not grow the queue indefinitely - this requires adding an integer counter to keep track of how much capacity and how many elements are currently buffered

Because of these extra states to track, the multithreading scenario got more complicated - we could have threads waiting on “receive” (when the channel is empty) or waiting on “send” (when the channel is full) while another thread calls close(); this needs some special care in our send/receive functions:

T receive()

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> the_lock(m_mutex);

m_cv.wait(the_lock, [this]

{

return !is_empty()|| !is_open();

});

if (!is_open())

throw std::runtime_error("Channel closed while receiving.");

T val = std::move(m_data.front());

m_data.pop_front();

m_cv.notify_all();

return val;

};

void send(T&& val)

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> the_lock(m_mutex);

m_cv.wait(the_lock, [this]

{

return is_open() && has_capacity();

});

if (!is_open())

throw std::runtime_error("Channel closed while sending.");

m_data.emplace_back(val);

m_cv.notify_all();

};

// Helper functions

bool is_open() const {

return m_open;

}

bool is_empty() const {

return m_data.empty();

}

bool has_capacity() const {

// m_capacity is a protected member variable that is set in the constructor

return (m_data.size() < m_capacity);

}

size_t capacity() const {

return m_capacity;

}

size_t size() const {

return m_data.size();

}

With these changes (and the return of the cv.wait on the send), there are now another terminating condition for the methods - which results an exception being thrown due to the channel being closed:

In this diagram, we can see that the send/receive have very similar control flow, but ultimately, it either results in an success or an error.

Final Test

With the above capacity, open/close changes, here’s a final test of the buffered channel where we send 8 items through a channel with a capcity of 3, we also add a 2s delay on the 4th item to test the synchronization. The output of this test is below:

Channel created.

Buffered channel constructed (3)

main thread: calling receive:

send thread: sending ping 0

send thread: sending ping 0 done

send thread: sending ping 1

send thread: sending ping 1 done

send thread: sending ping 2

send thread: sending ping 2 done

send thread: sending ping 3

send thread: sending ping 3 done

send thread: sending ping 4

main thread: received ping 0

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 1

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 2

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 3

main thread: calling receive:

send thread: sending ping 4 done

send thread: sending ping 5

send thread: sending ping 5 done

send thread: sending ping 6

send thread: sending ping 6 done

send thread: sending ping 7

send thread: sending ping 7 done

send thread took 2 s.

main thread: received ping 4

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 5

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 6

main thread: calling receive:

main thread: received ping 7

Note on the ping 4, we added a 2s delay, during that time, the main thread receiving the messages caught up and then waited for the pings, exactly as we designed.

Extra Embellishments

The basic functionality of a buffered channel is now in place, but we definitely still have plenty of rooms to improve.

Looping over the channel

in Go, it is very conveinient to setup a loop as a sink to some data being fed asynchronous into a channel as such:

for msg := range messages {

fmt.Println("got: " + msg)

}

If the channel is closed, then this for loop gracefully exits.

To mimic this behavior in our C++ channel

while (channel.is_open())

{

try {

auto item = channel.receive();

// do stuff with item

}

catch (const std::runtime_error& e)

{

// shutdown called

break;

}

}

Although this is not as terse as the Go option, I felt leaving this loop behavior in this state is a good trade-off between ease-of-use and code complexity, we can maybe make a special iterator that terminates in some special way by hacking the begin() and end() implementation, but that seems too much of a deviation from what we are trying to do here.

Combining Default Channel with Buffered Channel

If you have noticed, the simple channel in part 1 has different send/receive logic than the buffered channel we just built.

To reconcile the differences, we can either do it at runtime or at compile-time. The runtime option basically involves a bunch of if/else statements in the send/receive operations; but that’s an inelegant solution for modern C++. So we’ll attempt the latter, combining both single element and multi-element channels via template class specializations. We use a SFINAE trick here:

The Range struct defined here is used as a dummy type to achieve template specialization lookup. Basically, Range<true> and Range<N <= 0> are two different types, and therefore, the right implementation will be selected at compile time based on the second template argument N. The int N = 0 in the general implementation means that the channel capacity will default to 0 if left unspecified.

template<bool> struct Range;

template<typename T, int N = 0, typename = Range<true>>

class Channel

{

// default implementation goes here for buffered channel

}

template<typename T, int N>

class Channel<T, N, Range<(N <= 0)> >

{

// specialized implementation for a basic channel

}

To illustrate, we construct two channels, one with template argument specified and one without. We also added a small print in the constructor to help us distinguish the two. The output is attached inline:

Channel<std::string> chan;

Channel<std::string, 8> chan2;

// Output

Basic channel constructed

Buffered channel constructed (8)

One thing to note, the two channel implementations should ideally have identical interfaces - i.e. the helper functions that we defined size(), capacity(), is_open(), is_empty() should ideally be also availbale in the basic channel. Otherwise, you might get some cryptic compiler errors with a bunch of random template parameters that makes it hard to figure out what went wrong. Or, depending on your goal - that might be exactly the right behavior (have compiler figure out something you are not supposed to do for you)

Note on the choice of STL container

In this exercise, I opted for a std::deque<T> instead of a std::vector<T> or std::list<T> assuming that the elements we store will be move-constructable and assignable. This is a very important assumption that will be critical to getting good performance. If we assume that the items being stored in the buffered channel has already been constructed elsewhere, using a dequeue makes sense since it simplifies book-keeping and also incurs minimal costs. A ring buffer would also work in this scenario and can be easily implemented via std::vector.

Summary

In this part 2 of the Go channel series, we made a buffered channel, tested to make sure it works, and then integrated the basic channel with the buffered channel under the same unifying template interface via some SFINAE specialization tricks. In the next series - we will look at how to implement select/case and try some test scenarios with our C++ channels.